Über die zensierte Ausstellung FERROR und Bezüge zu Jelinek

E-Mail-Gespräch mit Silke Felber

Das Hauptmotiv der Märtyrer ist die reine Liebe zum Gesetz. Aber die Märtyrer sind doch die andren? Das sind doch solche, die sich in die Luft sprengen und möglichst viele mitnehmen wollen? Unschuldige? Man sollte grundsätzlich nur Unschuldige in den Tod mitnehmen, mit den Schuldigen passieren nach dem Tod so schreckliche Dinge, die sollte man ihnen ersparen. […] Schmetternd wirft der jeweilige Gott seine treuesten Anhänger ins Absperrungsgitter, zerquetscht sie wie Läuse, zertrampelt sie. Und das alles nur, weil er diesmal nicht gewonnen hat! Der Unterschied ist nur: mein Gott hat recht. Mein Gott ist ein wiedergeborener Christ, und er kann noch einmal und noch einmal geboren werden, das ist ja das Schöne an ihm als Christ. Und noch besser ist, daß er die Logik der Ungläubigsten und die Moral der Ungläubigsten auch verwenden darf, um zu beweisen, daß nur er recht hat und nur er recht schafft und die Dinge als unwiderlegbar darstellen kann und überhaupt . Er darf alles. Er darf alles, mein Gott.

Elfriede Jelinek: Bambiland[1]

Silke Felber: If god „can do anything“[2], as it is written in Bambiland, what can do art? And what is obviously prohibited? In which sense has in your exhibition FERROR been taboo barriers? Could you briefly explain the concept and go into sanctions regarding this exhibition?

Galina Bleikh, Lilia Chak: Art is multifunctional. One might say that it is a projection of civilization into our world, humanity reflecting upon itself, a prophetic vision, a critical conceptualization of reality, a practice, a means of communication, etc. On the other hand, art is an effective means of manipulating individual and mass consciousness, business, money, hierarchical institutions, a battlefield between individual ambitions, etc. Every person has his own set of art-related expectations. Some regard art as a decoration, meant to please and entertain. For others, the function of art is to detonate the public consciousness, exposing the wounds of society. In accordance with these differences, „taboo“ is not a fixed or permanent category – whether within an individual consciousness or in the context of various cultures or subcultures. Ultimately, everyone projects his own consciousness into what he sees, perceiving his own reflection in it. Art is indeed capable of everything, whereas the spectator is limited by his own conditioned corridor of perception. Taboos cannot exist without the spectator.

- Galina Bleikh, Lilia Chak: FERROR, 2009

We tend to think that nothing is forbidden to the artist, in the same way that nothing is forbidden to the individual consciousness. However, when an artwork enters the public space, it inevitably becomes a distorting mirror, reflecting common perceptions. If art infringes upon the values that are related to these perceptions, the public always receives it with hostility and aggression, as was the case with our „Ferror“ exhibition.

„Ferror“ is a new term that we have introduced into the international lexicon. We use this word to denote a new 21st-Century phenomenon: female terror. In English, there is no separate word for a female terrorist, so we had to create a new term that would reflect this concept as accurately as possible. This is a relatively new subject for modern art, and this makes the exhibition particularly relevant to our times.

Nowadays, the world faces a new gender-related challenge – we are being killed by female suicide bombers. Such terrorist attacks are relatively easy to set up: the female terrorist doesn't need to receive combat training or learn advanced security techniques. Essentially, she is turned into a cheap and disposable weapon that can be used only once.

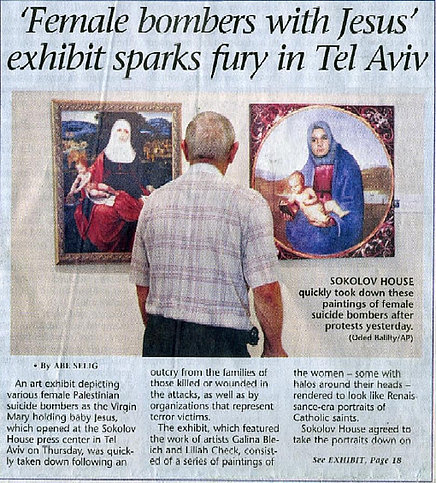

The ideologues of terror are masters of political strategy; they are adept at manipulating the public consciousness. If the mass media were to ignore terrorist attacks, nobody would invest so much money and effort into staging the show that is known as „terror“. This show would not exist without the spectators. The modern terrorist only needs to press the button that detonates the bomb to set the media mechanism in motion. The response of media outlets to current events is almost automatic. The banning of our exhibition was yet another trigger for the global mass-media, since this event was reported by virtually all the press agencies in the world.

Unlike art, mass media is neither an instrument for in-depth analysis of phenomena nor a way of expressing one's individual artistic interpretation. For this reason, media reports are not greeted with such a hyperemotional reaction. Nobody would ever blame a journalist for reporting that, in such a place and on such a day, a female terrorist detonated her suicide belt, taking such-and-such number of people with her into the grave, and for adding a couple photographs from the crime scene to his report. The newsreel violates no taboos. Our decision to open the „Ferror“ exhibition at the Tel Aviv Journalists' House („Beit Sokolov“) was a challenge to the media. The media focuses on the latest events, reporting them in captions and headlines, but yesterday's news is no longer newsworthy, and it is replaced by today's news. In our consumerist society, information is a product like any other.

Unlike the media, art has unique capabilities that facilitate a critical discourse, since it possesses the means and tools for comparing and analyzing phenomena in a historical perspective. This helps us to conceptualize our own time against the background of global history.

While creating the exhibition, we focused on seven terrorist attacks that had been carried out by female shahids: in addition to the seven „controversial“ pictures with the Madonnas, our exhibition includes seven canvases covered with soil from the scenes of the attacks. These works are a testimony of the wounded land – which is, essentially, our own body: after all, we live in this land, and we regard it as our own. When the body is injured, we feel pain. The third section of the exhibition is a video recording: Lilia Chak filmed those locations in Isreal from which Galina had taken the soil for her works. These are the places where the seven female terrorists had carried out their attacks. Nowadays, life goes on in these places, the sun is shining, people are bustling about their daily business, and only the memorial plaques listing the names of the victims remind us of the fact that acts of mass-murder took place here.

In the early morning of September 3, 2009 – the day on which our „Ferror“ exhibition was supposed to open (but never did) – our telephones were ringing constantly. We were hunted by journalists, radio show hosts, representatives of various TV channels, and other media outlets – both Israeli and foreign. They all asked the same question: „why did you canonize the image of the female Arab terrorist, proclaiming her a saint?!“

The still-unopened exhibition managed to infuriate virtually everyone. Relatives of terror victims, represented by the „Almagor“ society, were ready to sue us for hurting their feelings, and we were prevented from stating our position on a talk show on the Israeli Channel 1. The expression „Holy Terrorists“ was even mentioned in the press – it was the title of an incensed editorial in Yediot Ahronot (Israel's major daily newspaper). „Female terrorists are monsters; they must not be depicted as heroes!“ – proclaimed Yossi Tzur, whose son had been killed in a bus bombing in 2003. He submitted a complaint to the police, claiming that the exhibition constituted „incitement to violence“.

On September 3, we received a letter from the lawyer of the Israeli Journalists' Association, informing us that the pictures would be removed from the exhibition.

Then, we were subjected to massive pressure from the Israeli public, and later – following reports in international news outlets – international public opinion added its voice to the chorus of condemnations. The Associated Press agency spread the information about our exhibition among media outlets worldwide, and we became the object of global attention. A powerful wave of hatred, aggression, threats, and misunderstandings washed over us, directed by numerous bloggers, journalists, and even personal acquaintances. Our email addresses and telephone numbers were publicized on the Internet, and we received numerous unpleasant messages. Frankly, this outpouring of hatred was hard to endure psychologically.

This was our encounter with the problem of distorted interpretation of artistic works by society. Notably, the list of „offended“ parties included practically everyone: terror victims, Christians, Jews, Muslims, secular individuals, both educated and uneducated people. Even Yuli Edelstein, the Israeli Minister of Information, gave an accusatory interview in the context of our works, saying that „democracy must be protected from this kind of art“. Ofir Akunis, a Likud MK, stated that „this is a slap to the thousands of Israelis who were targeted by terrorists like the ones that are depicted in these images. Freedom of expression must have its limits“. Apparently, we must have touched some very deep and painful nerve in the public consciousness to provoke such a powerful response to „mere“ images.

Silke Felber: In Margit sagt, second part of Babel, Elfriede Jelinek presents a Janus-faced „character“ between Madonna and the mother of the Moslem martyr Mohammed Attas who on September 11th 2001 directed the airplane into the WTC. In the exhibition FERROR you two, Mrs. Bleikh and Mrs. Chak, equip Christian Madonnas with the faces of female Palestinian suicide attackers. Did Jelinek inspire your artistic work in any way? Would you say that you maybe have similar intentions?

Galina Bleikh, Lilia Chak: It is said that ideas are floating in the air. We and Elfriede Jelinek are on the same morphological plane – a plane where these connections must exist on some higher levels.

- Foto of an 18 years old suicide bomber which was sent to Bleikh and Chak

Interestingly, modern Palestinian women fit neatly into the traditional image of the Madonna, because of their common headgear, which is reminiscent of the headdress of the Virgin Mary as she is depicted in the paintings of Renaissance masters. We would often be reminded of this analogy when we witnessed Arab Jerusalemites in the streets of the city. Some of them possess remarkably beautiful faces. Incidentally, Christians should also find such an image appealing, and it should not fill them with xenophobia and the desire to deprive the Arab women who reside in their countries of this Christian-like headgear. When an image depicting the severed head of an Arab terrorist, lying on the sidewalk after a suicide attack (see illustration above), was emailed to us and appeared on our computer screens, the idea of merging the image of the Madonna and the face of the female terrorist came unbidden into our minds.

This woman detonated herself on bus 25 in Jerusalem. Galina Bleikh used this bus line for her daily commute, and Lilia still lives near the crossing where the attack took place. In other words, this event took place within the real space of our lives.

In our images, as in Jelinek's works, the collision between different contexts leads to ambiguous meanings. A Madonna with the face of a Palestinian terrorist – what does it mean? Is it a hymn to martyrdom, or the monster of our time? The spectator, upon encountering the ambiguous interpretation of the idea, the lack of dichotomy, is inevitably filled with aggression, which is directed at the work and at its creator.

- Giovanni Bellini: Alzano Madonna, 1485-1490

- Leonardo da Vinci: Madonna Conestabile, 1502-1503

Silke Felber: Similar to Elfriede Jelinek, in your work you deconstruct existing material, using for example works of Bellini, Botticelli or Raffael. Are you aware of any subversive potential from this and do you find also here connections to Jelineks procedures? Can the fact that you work with existing work of art be seen as a breach of taboo? Have there been reproaches for abuse that assumed a desecration of those works of art?

Galina Bleikh, Lilia Chak: We are convinced that the language of modern art is based on interacting with the entire field of images that have been created by human culture, without any limitations. In this sense, every artwork may be seen as a simple image that may be analyzed, deconstructed, presented in a different context, etc. The modern museum transports the image of the Madonna (and of other saints) from the sacred space into the everyday, profane context. Seen in this light, our works break no taboos.

In this sense, the approach of Elfriede Jelinek, who allows herself to speak of idols from the level of desacralization, is related to our works.

The public consciousness always contains a level of conceptualization whereby certain notions, images, and symbols are endowed with supreme value. In such cases, any attempt to think of them in a different context is inevitably perceived as a crime, with all that follows.

Silke Felber: What is your general attitude to Elfriede Jelineks (always „taboo-crossing“) works? Are they, especially as explicitly „feministic“ works, important for you and if so, in which sense?

Galina Bleikh, Lilia Chak: We do not regard ourselves as followers of feminism – or any other movement, for that matter. This is our principled position! Any ideology – whether leftwing radicalism or rightwing conservatism, regardless of its content - provides its adepts with a package of values, all of which must be espoused simultaneously. If you care about the fate of same-sex couples, you must also sympathize with the oppressed Palestinians and be opposed to globalization (or the other way round, it doesn't matter). If you are a nationalist, you must loathe foreign workers and modern art.

We do not like the fact that feminism forces one to take part in a constant war between the sexes. It reaches the height of absurdity in denying the differences between the ontological purposes of men and women. At the same time, we are grateful for the fact that, nowadays, we women can lead full social lives, achieving self-realization in the workplace and in our creative endeavors. Undoubtedly, this is the result of the struggle that feminists have waged throughout the previous century, gradually shifting the public consciousness in the direction of female empowerment. At the same time, we feel close to the ideals of the so-called traditional society, with its conceptions of femininity, motherhood, and love. Instead of a gender confrontation, we strive for harmony between the sexes, which would be based on the principles of the traditional Jewish family – principles that go back to the Torah. We regard these principles as compatible with the ideology and language of modern art, which we practice. For instance, we have no fear of overt sexuality, provocation, or a liberal approach to the sacred. However, those who usually control the institutions of contemporary art – curators, gallery managers, art critics – tend to have a narrow-minded leftwing worldview, which makes them reject any deviations, such as religiosity or Zionism. Thus, instead of freedom and democracy, the hypocritical and so-called „open“ Western society presents us with a black-and-white, dichotomizing approach to the world, designating this approach as „personal freedom“. The development of these kinds of ideas is well-financed through university programs and various foundations.

We are convinced that the world is moving towards ever-increasing polyphony. The combination of incompatible concepts within a diversity of forms, greater ambiguity – we regard these things as an expansion of consciousness, which is appropriate to present-day reality.

In our opinion, the value of Elfriede Jelinek's work cannot be reduced to mere feminist ideology. Her works contain numerous meanings, some of which contradict each other. We regard it as a wonderful thing. The problem is that people often tend to aggressively reject this kind of message, precisely because such a message – the multiplicity of meanings and the conflict between them – provokes the most intense discomfort.

Silke Felber: In FERROR you use the sujet of Madonna and its symbolism of motherhood and mother love and put it in contrast to the murdering female suicide attacker by asking „How can a woman who comes into the world with the role of loving and giving life become a source of hatred and murder?“[3] Don’t you maybe reproduce a religious shaped idea of women by that?

Galina Bleikh, Lilia Chak: Women who commit terrorist attacks are primarily victims of the religious and patriarchal Muslim society. As we all know, most of them either conceived out of wedlock after being raped, or – conversely – were unable to conceive and bear children after being married. From the point of view of the ideologues of terror, they are sinners who deserve to be scorned and killed. However, by turning themselves into „iving bombs“, killing both themselves and the „enemies of Islam“, they automatically become righteous women, gaining the status of „saints“ in certain segments of Muslim society. This is yet another aspect of the images that we have created.

„Society simultaneously scorns and exalts the role of the mother, which naturally leads to distorted manifestations of female power – this, in my opinion, is extremely unfortunate“[4] – said Jelinek in an interview.

On the other hand, every psychiatrist will tell you that Elfriede Jelinek herself is, unfortunately, the victim of a very strained relationship with her own mother. During her childhood, Elfriede did not receive sufficient motherly love and affection, and she never enjoyed a harmonious family relationship. This childhood left a mark on the rest of her life, setting into motion a mechanism of hate and leading to the inability to feel happiness. Alas, Western culture, with its extreme individualism, leads to the proliferation of this type of victimhood.

We are convinced that the religious consciousness (including Judaism) contains an important element of treating the woman as the origin of all living things, an inexhaustible source of love and motherhood. It would be very unfortunate if we were to throw the baby out with the bathwater – i.e. lose the basic concept of the creation of the world in our struggle against religious patriarchy and bigotry.

- Selig, Abe: ,Female bombers with Jesusʻ exhibit sparks fury in Tel Aviv. In: Jerusalem Post, 4.9.2009

Silke Felber: The Israeli representative Yochanan Plesner called your exhibition „a despicable public relations ploy“[5]. The reporting of Elfriede Jelinek´s texts or rather their performances shows similar labeling. What do you answer to such reproaches?

Galina Bleikh, Lilia Chak: Obviously, a provocative statement is always a public relations ploy. At the same time, it is also an effective means of reaching out to others, of making oneself heard. And if you have something important to say to the world (as Elfriede Jelinek most certainly does), such a „public relations ploy“ cannot and should not be regarded as a „despicable“ act.Incidentally, we didn't expect our exhibition to have such a powerful global resonance. Therefore, we cannot be accused of being cynical and calculating. The shocking images were, for us, a way of conveying our own shock at the phenomenon of female terrorism – a phenomenon that we, as Israelis, have often encountered in our real lives.

Silke Felber: Elfriede Jelinek again and again is reproached for impiety concerning the presentation of culprits and victims. Also against you it was hold to offend and embarrass the relatives of the numerous Israeli killed by the suicide attackers. „[…] at least a monument you can try to build for the victims. […] at any rate you have to grasp the inconceivable.“[6]- Elfriede Jelinek defended her position (in this case concerning Babel). Would you agree to this statement?

Galina Bleikh, Lilia Chak: Each tiny step in the conceptualization of terror is a new, unflattering message about us, its „victims“. If we were to depict the female terrorists as mere „monsters“ or „saints“, the exhibition would have aroused much less controversy. However, we made a conscious decision not to simplify the image, since we felt it was important for our work to reflect the multiplicity of meanings and the conflict between them.

Incidentally, Elfriede Jelinek's works are characterized by the same multiplicity of conflicting meanings. They fill the reader with constant suspense, drawing him into the text.

Silke Felber: Which taboos characterize the contemporary Israel and which role would you say takes in this context women’s art as a taboo breaching instance?

Galina Bleikh, Lilia Chak: Israeli society is notable for its pluralism, which exists within a national homogeneity. This paradox is the unique, inimitable feature of Israel. This country is home to immigrants from various countries and in various generations, who live together (but do not always get along). The degree of religious diversity within Judaism is immense – from Ultra-Orthodox Jews, who deny Israel's right to exist, to religious Zionists. Secular and emancipated Israeli women serve in the army (where they command platoons of men), wear bikinis, and visit bars and discos, while the „downtrodden“ women wear wigs, walk in the streets covered from head to toe, and do not use the Internet. In such circumstances, any extreme action (in whatever direction) may be perceived as the violation of some taboo. At the same time, there exists an unspoken status quo that enables each group to exist within its own social niche.

Our exhibition has upset this order, stirring up the whole of Israel.

19.11.2013

Galina Bleikh graduated from the Stieglitz St. Petersburg State Academy of Art and Industry, Russia (MA). Since 1993, she lives in Jerusalem. She participated in over 40 solo and group exhibitions in Russia, Israel, USA, France, UK, Germany, and in several international festivals of performance art. Among them, the International Triennale of Contemporary Art (Osaka, Japan, 2001) and two Moscow International biennales of Contemporary Art (2005 and 2007). In 2008, she was awarded the first prize at the art competition (among 18,000 entries), organized by Cellcom company. Since 2010, Galina Bleikh works together with Elena Serebryakova.

Website: http://www.bleikh-art.gala-studio.com/

Lilia Chak graduated from the Stieglitz St. Petersburg State Academy of Art and Industry, Russia (MA). In 1985–1986, she was awarded the first prize for „The best research work on art“ by Russian Ministry of Culture. Since 1990, she lives in Jerusalem where she founded in 2002 her design studio, GalaStudio, for art projects, graphic design, industrial design and interior design (together with Galina Bleikh). In 2009, she was awarded the first prize at the art competition (among 18,000 entries), organized by Cellcom company. Website: http://www.chak-art.gala-studio.com/

Anmerkungen

[1] Jelinek, Elfriede: Bambiland. Reinbek: Rowohlt 2004, S. 75.

[2] Jelinek, Elfriede: Bambiland. Ü: Angelika Peaston-Startinig, Jennie Wright. http://a-e-m-gmbh.com/wessely/fbambie.htm (19.3.2013), datiert mit 21.6.2004 (= Elfriede Jelineks Website, Rubrik: Archiv 2004, Theatertexte).

[3] Teibel, Amy: Israeli art show removes pictures showing suicide bomber as Virgin Mary after public furor. In: The Gaea Times, 3.9.2009.

[4] Jelinek, Elfriede: Interview. http://noblit.ru/node/1008 (17.11.2013), Ü (from Russian to English): Galina Bleikh / Lilia Chak.

[5] N. N.: Israel: pictures of St. Mary as terrorist removed. In: NewsOk, 3.9.2009.

[6] Jelinek, Elfriede: Es geht um Medien, Pornographie und Krieg. Elfriede Jelinek über „Babel“. In: Programmheft des Wiener Burgtheaters zu Elfriede Jelineks Babel, 2005. Ü: Julia Schwarz.

ZITIERWEISE

Bleikh, Galina / Chak, Lilia: „We and Elfriede Jelinek are on the same morphological plane“. Über die zensierte Ausstellung FERROR und Bezüge zu Jelinek. E-Mail-Gespräch mit Silke Felber. https://jelinektabu.univie.ac.at/religion/interreligioese-stoerungen/galina-bleikhlilia-chak/ (Datum der Einsichtnahme) (= TABU: Bruch. Überschreitungen von Künstlerinnen. Interkulturelles Wissenschaftsportal der Forschungsplattform Elfriede Jelinek).

Elfriede Jelinek

Texte - Kontexte - Rezeption

Universität Wien

Universitätsring 1

1010 Wien

T: +43-1-4277-25501

F: +43-1-4277-25501